How to practice optimism

Soothing a fussy soul

Last week, I gave birth to a perfect little angel human.

So perfect, little, and angelic, in fact, that for a few days a vindictive grief stabbed my heart every time I looked down at Mari Jr.

I haven’t had much experience with babies, so I was totally unprepared for a rigorous study in contrasts as soon as I saw my own baby: A pure innocent helpless infant (wrapped in a pastel Pooh blanket, at that) in my arms on a hospital bed—juxtaposed with the scary loud harsh world outside the hospital window.

After staring at my child, I could barely stand to look outside; after staring out the window, it caused me pain to look back down at this tiny beautiful thing.

The hospital generated a safe cocoon for a couple days and I would have chosen to stay there forever, even with its relentless beeping, an annoying IV, and soggy sad cauliflower entrées on cafeteria trays. I’d gladly take all of it!

In Baby Hospital World, every bandage has Bambi on it and the newborn hats have bear ears on the top. Duckling cartoons decorate the most important forms, and a colorful balloon font adorably reminds us to stop by the birth certificate office before discharge. The nurses wear scrubs with an elephant-mom-and-baby pattern on them, and even the intimidating pediatrician barges into the room with a stuffed lion in tow.

Everything is soft and cute. When the little one had to stay a night in the NICU, the wing was still within the confines of the cozy hospital where EKG electrode stickers are heart-shaped and night nurses sing lullabies.

Just let us stay here, I thought, as we packed up to go home (a whirlwind, multi-hour process that as frantic and high-stakes as preparing for a surprise around-the-world journey we had just won and had to embark on immediately).

But the hospital wouldn’t let us move in.

Instead, we had to take this itty bitty floppy being down the non-soft, non-cozy elevator, and into the world (a humid grouchy New York one, at that).

Everything presented an imagined threat: the sound of construction, the smell of our driver’s cologne, the sight of a concrete skyline that once looked so elegant and now appeared menacing. Too big, too scary, too Bambi-less.

How do I deal with this, I thought, buffering my C-section scar with a pillow as our driver seethed at the truck who pulled ahead of us on the six-lane parkway notorious for risky maneuvering. I wanted to buffer my mind with a pillow too.

Ever since we took the angel home, I keep hearing about “muscle memory.”

All the stuff we’re learning that seems impossible to remember will “soon be muscle memory.” In a couple weeks, apparently we won’t even have to think about it; these motions and routines will be second-nature.

If we ever start doubting ourselves, so we’re told, we can rely on muscle memory and intuition. We probably had it right the first time.

And indeed, I’ve noticed that the baby only fusses when I’m going through a mental checklist that turns instinct into a cerebral exercise. “I need to do this, followed by this, followed by this…” until we’re both frustrated with me.

When I literally lean back and do what just feels good—or at least not totally robotic—then I can experience mom-of-newborn bliss and the infant in my arms can trust that they have a halfway competent mother.

Both our bodies relax, and I feel a lot less stressed about the scary world outside. Muscle memory kicks in for me, but it’s the muscle memory of faith.

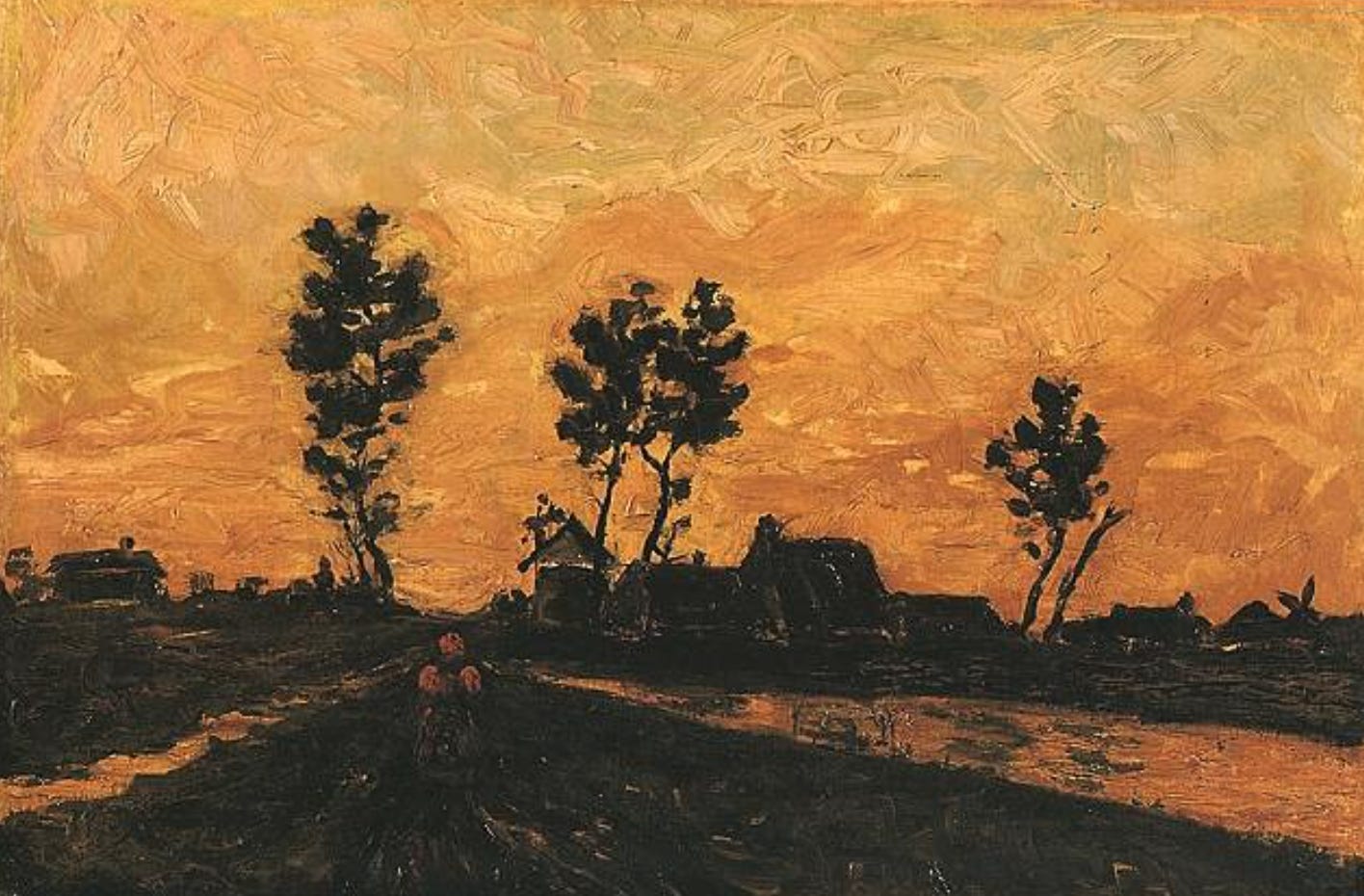

A few years ago, I watched that depressing Van Gogh movie, which perfectly starred Willem Dafoe as Vincent the complex, awed, and unwell painter.

I didn’t understand a lot of it (you lose me as soon as dream sequences get involved…), but I DID take away that I wouldn’t have lasted more than two minutes in late 1800s France without being put in a straightjacket myself!

No doubt that Van Gogh, like so many of our treasured ‘tortured artists’ from history, most likely had a suite of undiagnosed mental afflictions that we’ll never know for sure.

And, I got the sense that the one affliction that kept getting him sent back to the hospital, was…being sensitive?

Getting his feelings hurt easily and being easily moved by a sunset seemed like the most ghastly traits to the specific society he was living in, where such spells of emotion belonged to the mysterious world of the earthly feminine—not the reasoned world of the ascendant masculine.

As I wrote about in my most recent book (and yes I do feel self-conscious writing that!), one of history’s biggest bummers is that Imperial and Enlightenment thinking pitted Nature and Humans against one another.

Nature was unpredictable, sinful, and lawless; civilized humans were logical, rational, and orderly.

People who were a little too in touch with their natural side were thus placed in a category somewhere between animal and person.

“They’re ‘human,’ we guess, but not AS human as the guys who write books and come up with philosophies.”

“Maybe it’s best we stash those weirdos in an institution”

…So went the ‘logic’ of the time.

Anyone who prioritized the nudges/rhythms/enigmas of nature over the rules of the civilization were a danger, and considering them as less-than-fully-human was a convenient excuse to lock them away.

(See also: reasoning for enslavement, misogyny, colonization, etc.)

In late 1800s Arles, and much of the rest of Europe, it seemed the world just wasn’t made for oddballs (or, as we say now, highly-sensitive individuals). Best to keep them in a locked room forever, right?

And it wasn’t just oddballs getting banished to institutions, but anyone whose ratiocination collapsed under grief, empathy, disease, pregnancy, and any other state of being that threatens emotional order with its unpredictability and natural-ness.

At the end of the depressing Van Gogh movie, there’s the Van Gogh song gorgeously performed by Lianne La Havas.

It’s a stirring, sad sad song, and by the time Lianne took us to the final verse I was a puddle:

And when no hope was left in sight on that starry, starry night

You took your life, as lovers often do

But I could have told you, Vincent

This world was never meant for one as beautiful as you

I had to take a two-hour walk just to cool down from that.

But after I did, and allowed it to touch me deeply as I blasted it from my headphones while dodging young coruscating drunk people on a bustling Friday night in the East Village, I realized I didn’t agree with it.

How could I not “agree” with such a moving piece of art, you ask?

It’s that last bit at the end: The world wasn’t meant for him.

Waaaait a seconnnnnddd.

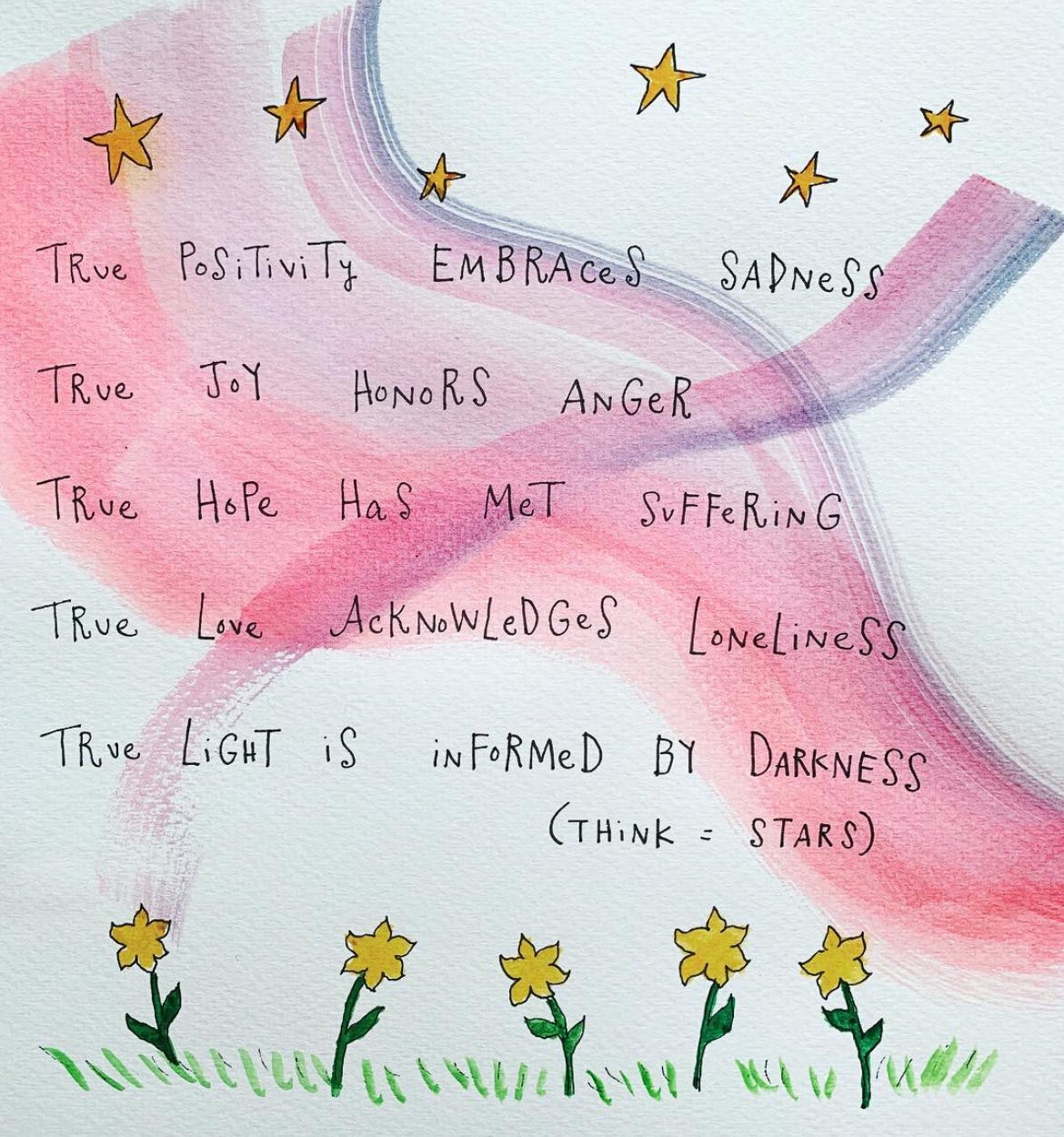

Societies throughout history have been so harsh, usually to protect power and hierarchy. But that doesn’t mean the world is harsh. The world is wonderful, and it’s usually the most sensitive among us who show us its wonders!

Maybe the world is even meant more for beautiful sensitive people like Van Gogh because they appreciate it with such attunement and attention! And they can point out all the splendors that the rest of us may miss.

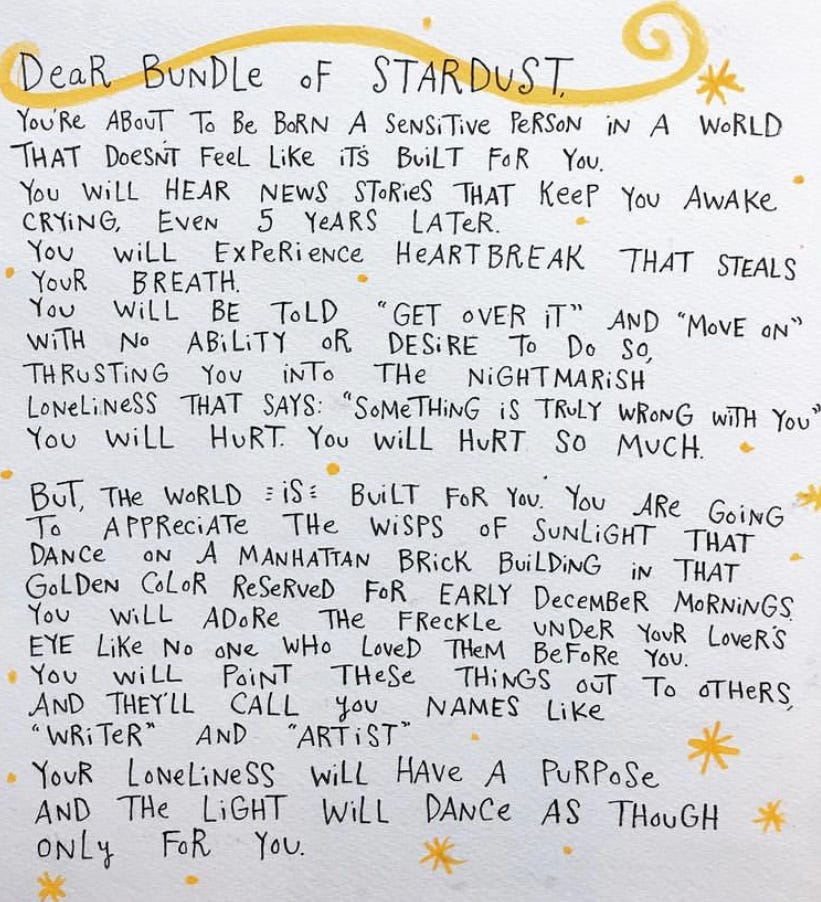

Later that night, I wrote this love note to a baby Van Gogh:

(I got quite a few comments congratulating me on “expecting,” which is funny considering that this was simply inspired by a Willem DaFoe performance. Who, now that I think about it, looks exactly like many newborns.)

Upon coming to this realization—that maybe the world was in fact meant MOSTLY for Van Gogh!!—I practiced a different perspective whenever a brain-voice started insisting that the world is bad.

Optimism, like any perspective, is a practice that relies on muscle memory to stay strong. It was hard—actually unfeasible at the beginning—to reroute my spirit toward the path of belief in a benevolent universe after I’d convinced myself that goodness was scarce here on earth.

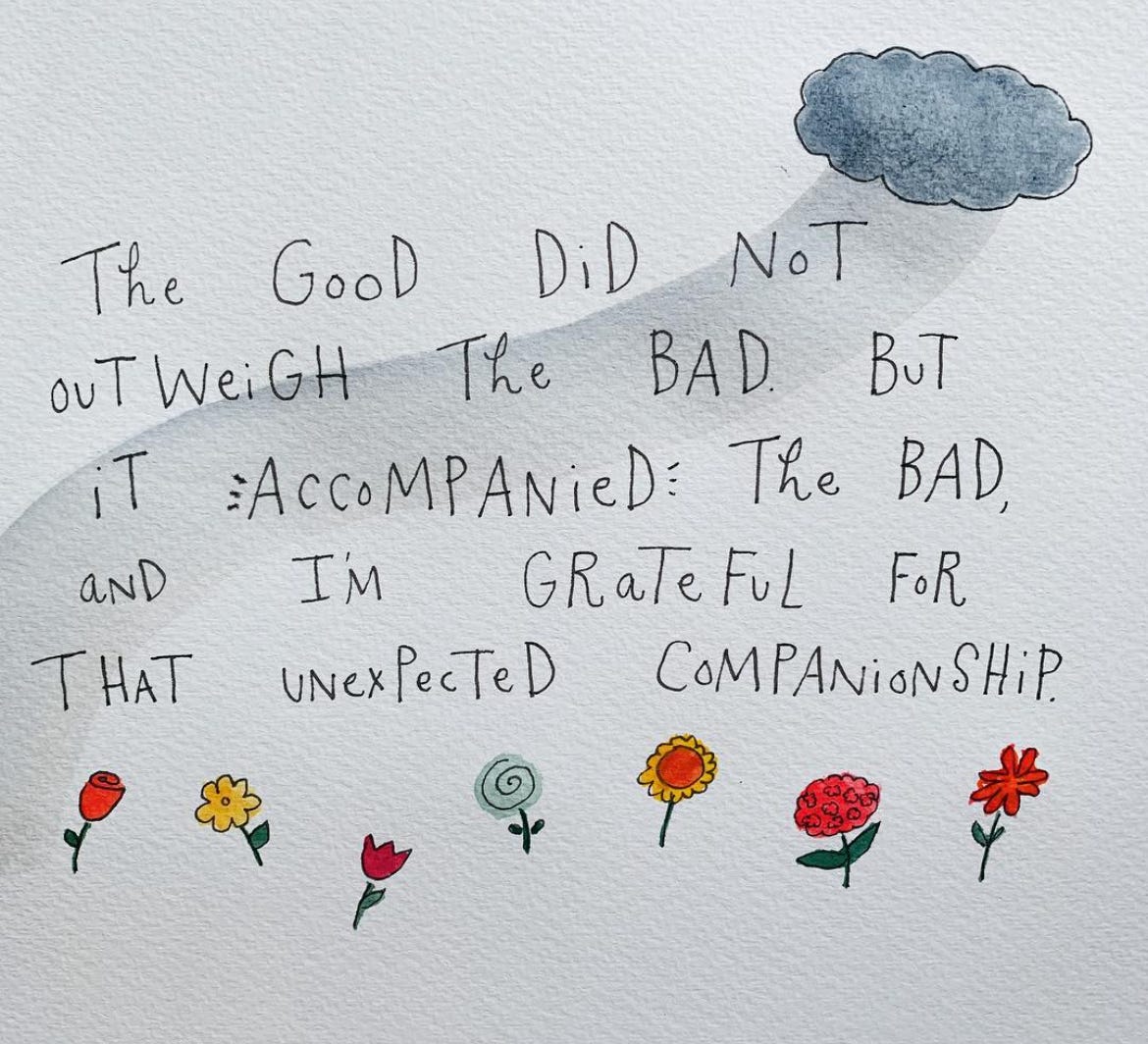

I resonate so much with this Anne Lamott quote:

Life is both a precious, unfathomably beautiful gift, and it's impossible here, on the incarnational side of things. It's been a very bad match for those of us who were born extremely sensitive. It's so hard and weird that we sometimes wonder if we're being punked.

I have wondered millions of times myself if coming to earth was the biggest scam, or if I accidentally arrived at the wrong planet, or if the aliens forgot to factory reset my soul when they sent me here, or if God got the wrong idea when I asked for an interesting life.

“This CANNOT be it,” I still think a few times a day.

Then I revert to muscle memory: This IS it.

At this point the rerouted path in my brain is actually the main drag:

People who are extra sensitive to the horrors of life are ALSO extra sensitive to the magnificence of it.

When Mari Jr was born, I could feel my insides ripping apart as they were pulled between the contrast of the perfect angelic innocent pure perfection in my arms, and the sharp-cornered scary big awful mean world outside. (Or was that my C-section ripping my insides?)

But after a couple days of that excruciating tension, it dawned on me: This baby is part of the world, too.

The sweetness and purity of this tiny critter isn’t an anomaly; the earth expresses those characteristics in all sorts of ways (think: daisies, chipmunks, mountain streams, children’s drawings).

I can’t contrast my baby’s goodness with the outside because the outside is filled with this too: babies and former babies alike who just want love and a Bambi band-aid over their immunization prick.

If I’ve learned anything over the past week, it’s that there is a vast world of pacifiers out there on the market. My baby already has their preference for the size and shape of this object I heretofore had never thought about for more than a fraction of a second.

Now, I find myself wondering how and why the pacifier was invented, and by whom, and how they’ve evolved over time, and how many options there are, and what they’re like in other countries, and plenty of other queries that would make my former self want to die from embarrassment.

But whenever I consider looking up any of those answers, I distract myself with the same sentiment: ‘Pacifier’ is such a lovely word.

I wonder why we don’t use it more (add that to my list of things to look up!).

If “self-care” had such wildly successful PR in the 2010s, how did the word/concept “pacify” not sneak in there, along with adult coloring books?

Surely a human of any age could use a pacify-er these days.

The most shocking thing about having a baby was just how easily life comes to a newborn. They know right away what to do to keep themselves alive and even happy being alive, as though they have built-in muscle memory.

Mari Jr knew exactly what to do with a pacifier immediately, for example. I pondered why my own self-soothing doesn’t come to me so easily.

My pacify-er of choice these early days of motherhood is to keep the concept of muscle memory in mind. You probably had it right the first time.

I know it works because I quickly experienced the muscle memory of faith. I couldn’t believe the goodness of this child could exist in such a world as this; then within a couple days I remembered that of course such goodness belongs in a world such as this.

Years of practicing optimism and rehearsing belief in a benevolent universe trained me to develop the muscle memory I need to reconcile my baby’s perfection with the outside’s failures. Or, at least remember how necessarily those extremes accompany one another.

A lot of philosophers from Plato to C.S. Lewis have argued that we all must come to earth from some original place of Goodness (e.g. heaven) because earth is so itchy and uncomfortable and never fits quite right.

We are born ‘homesick’ for a comfier place where we aren’t always freaking out about how hard it is to exist there. I’m guessing that place has Bambi band-aids and heart-shaped stickers and caregivers who sing lullabies.

I believe that place exists and we’ll get back there someday, but for now we’re all existing beyond the pastel Pooh room and it feels strange because it is strange.

If I had designed the world, I would definitely have chosen a pink bow-wearing kitten motif to decorate the whole planet and assigned an assertive doctor to nuzzle us all with a stuffed lion when we get fussy.

But nobody left the world design to me, outrageously enough.

And so, for now, what we have is pacifiers: the glories on earth that make it bearable enough to live here and, through muscle memory, find an inner calm.

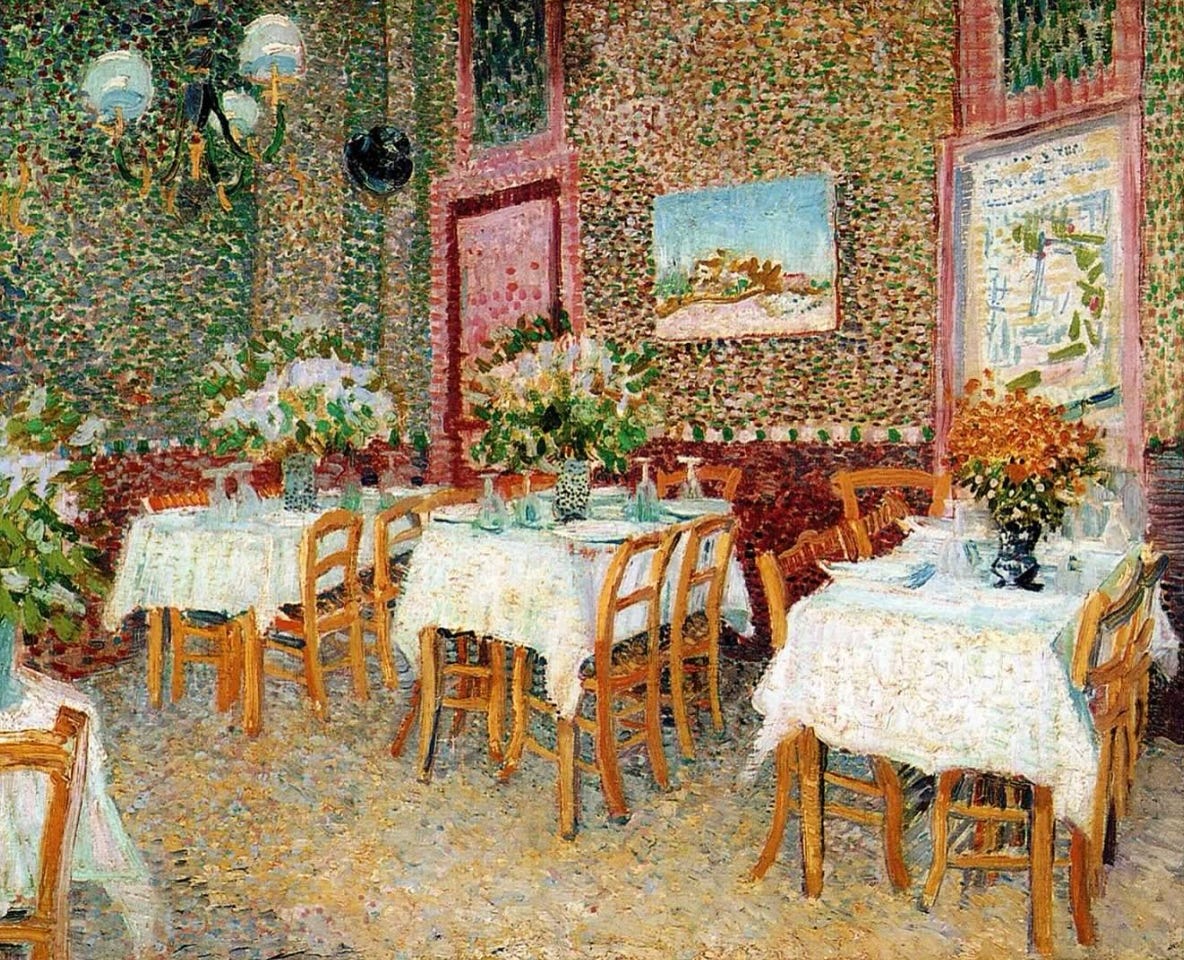

I’m guessing Van Gogh had a few:

“If you truly love nature, you will find beauty everywhere.”

-Letter to his brother Theo, June 1874

“I often think that the night is more alive and more richly colored than the day.”

-Letter to Theo, September 1888

“I have a certain faith in art, a belief that it will not only be a pleasure to look at but that it will also console.”

-Letter to Theo, July 1882

“What I try to capture with my heart is…something like the eternal, a deep reality, in the ordinary things: a potato, a peasant’s face, a bit of earth.”

-Letter, 1885

“What a simple thing is a chair, yet it can be as alive as a person. My own chair is like an old friend, full of character.”

-Letter to Theo, 1888

“I have tried to express the idea that those old boots, with all their mud and wear, tell more about the man who wore them than any portrait could.”

-Letter to Theo, 1886

“There is a kind of eternal beauty in the simplest things—in a jug, in a chair, in a pair of worn shoes. They have a life of their own.”

-Letter to Theo, 1885

My greatest hope is that this otherworldly, snuggly little person who is sleeping beside me can feel at cozy in the world even with its sharp edges and lack of pastel baby animals at every turn.

And I do think creativity is what makes us all feel at home here. So my bid to you, if you find yourself on the sensitive side of things, is to keep creating—whatever your medium—to add to the vast range of pacifiers, and point out the ones we might have missed.

Mari! Congratulations on having your baby <3 I'm so happy for you!!! Mari Jr is going to have the most kaleidoscopic experience of life, thanks to you. Thanks for sharing this piece, I really needed to hear this. I’ve been finding it hard to stay optimistic in the middle of life’s chaos. Even on days when I do feel happy, I can’t enjoy it fully because guilt creeps in. I start wondering what less privileged people would think about the source of my happiness—whether it’s ethically, politically, or socially ‘right.’ It feels like a kind of sympathy fatigue, where every thought has to include everyone else’s struggles. Instead of just allowing myself the freedom to feel what I feel, I get stuck questioning whether I’m even allowed to. So reading this gave me permission to make space for joy.

P.S. I'm still waiting to receive your book while I wait here in India. It's still cozied up in NY.

Dear Mari, How is it that your first newsletter after giving birth is a masterpiece?! I could not believe it , by the first paragraph I was all in and then it just kept getting better, and better, and better. It s a book! I receive so many newsletters these days - a good things, it's curated reading but I got to the point were i do not have time to read them all and I almost did not open this one . I am so grateful I did open it, but mostly I am grateful to you for writing it and sharing it with us. Truly inspiring. Pacifying. Everything. Congratulations, I am delighted for you and your wonderful family!