When I applied to my last office job, I decided to try a new thing as I wrote my resume and cover letter: I told the truth.

With a scattered work history (barista, tap dance teacher, men’s fashion writer), I would typically force a convenient narrative out of my work history, demonstrating that I'd clearly been building toward this job all along. I’d over-exaggerate some duties and completely leave out multiple years of work that detracted from my case.

Then one day on my job search, I found an interesting position in marketing. I knew I could handle all the responsibilities: create zippy copy, craft a strong message, come up with campaigns, and communicate in various ways to various groups of people.

The listing required a years of marketing experience and specialized training, but I just spent a decade learning how to communicate well from other types of work. I was sick of 'hiding' food service and retail on my resume because I worked much harder at those jobs than I've ever worked in offices, and I learned much more.

As Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez said about her former job as a bartender, "My 'unskilled' jobs taught me 10x more than my 'skilled' jobs ever did."

In my cover letter, I wrote boldly about how holding multiple jobs, working abroad, moving around, and using my spare time to pursue creative whims had prepared me splendidly for job in which the main task was to figure out how to speak to different audiences.

My future boss complimented my 'interesting, well-rounded path.'

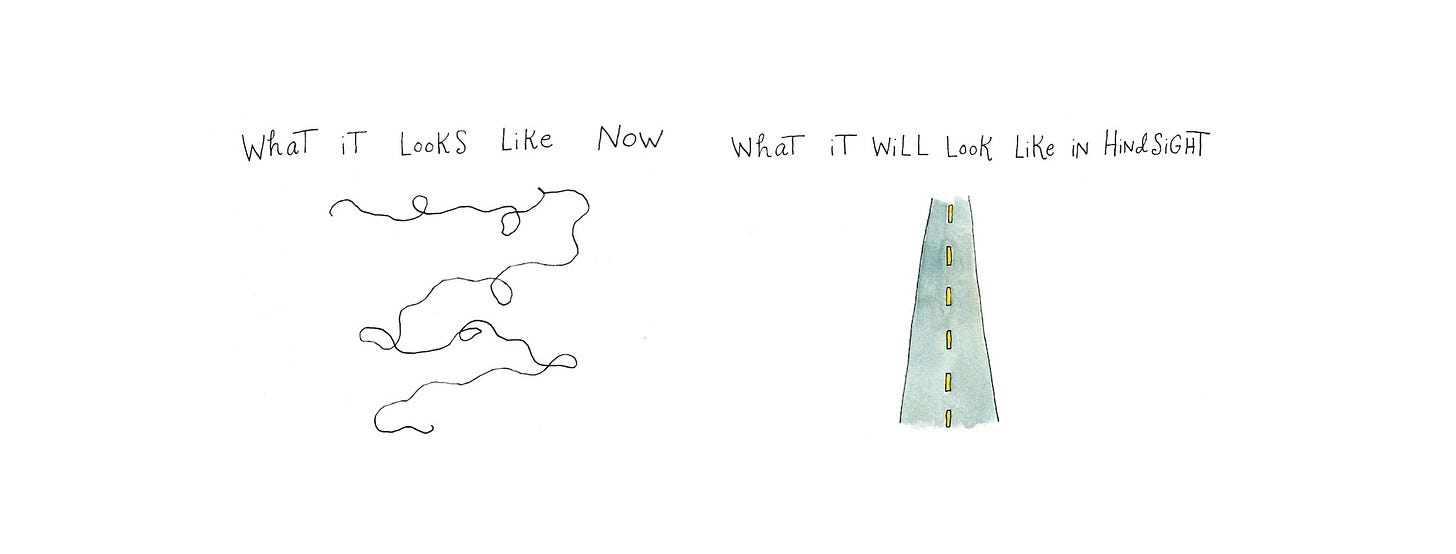

When I got the job, it first time I ever felt like my zigzag journey was a good thing, at least from a societal point of view. (I knew it was a good thing, from a Mari point of view). While I prioritized my own curiosity and adventures over bullet points on a resume, I felt insecure that those bullet points always carried more value.

Getting a job based entirely on all the things I thought were wrong with my path helped me think about my personality in a new way. It wasn't that I was lazy or distracted; I was just interested in so many things! According to my boss, this was an asset: I was adaptable, open, and good at learning quickly because I'm always learning quickly (before I move on to the next subject).

This realization directly opposed career advice I'd been getting since high school:

Pick a lane.

If you are a specialist, this is probably fantastic advice. But a lot of us are what Emilie Wapnick calls multipotentialites, someone 'who displays aptitudes across multiple disciplines,' or: someone who can't make up their mind, or can make up their mind but wants to be 25 things, or is easily bored/terrified by the idea of one single path, or might feel undisciplined because they start and stop new things all the time.

Picking a lane doesn't make sense for those of us who don't have to be somewhere by a certain time; it speaks to a different set of priorities that don't fit for a lot of people.

Emilie says in her TED talk that the idea of the one true calling is highly romanticized in our culture, so we might feel stressed as we try to figure out the great thing we must do with our time on earth to make sense of our own existence.

I used to search for mine like a bloodhound, singularly focused for a spell on cello or medieval philosophy or haiku-writing like my entire life depended on it. Sometimes I'd wake up in the night with an epiphany jolt: I'm going to work for public radio! I'm supposed to be a baker! It was an ambassador to Turkey all along! I must become a professor of Peace Studies! I'm going to start the first perfumery of its kind in this city! Everything was leading to me becoming a documentary maker! (These are all true examples.)

But then...I'd lose the spark, or something else would take its place. I looked around at people who had been on a fast track since high school toward one job and their linearity was so exotic to me. Like, are we the same species? Jealousy and bewilderment would overwhelm me at times.

I remembered a friend from college who majored in art history simply because it fascinated her. When asked, "What are you going to do with that?" she'd reply, "Not have a mid-life crisis." She's been a bartender with a part-time admin job ever since and her interest in art history is a sacred study only for her own afternoons and daydreams. She's also one of the happiest people I know, and I love how she's embraced her complexities.

Another friend of mine encouraged me to be enthusiastically blunt when anyone asked What do you do?: "I work at a store, and I want to be a writer, and I do yoga, and I cook myself a wonderful dinner every night." He promised it all belonged in my answer.

I comforted myself by reading stories about people who had done a great many things in their lives, like Julia Child who was an athlete, a copywriter, a top-secret researcher for the CIA who developed shark repellant for underwater explosives during WWII, and a housewife until she wrote a cookbook at age 49. This was my dream life: filled with stories and strangeness and pleasures.

As Julia followed her interests around, so would I. I always expected to have a series of oddball jobs that didn't make any sense in succession, while spending my free time as I pleased with fun creative pursuits and maybe stints in different cities.

A few years ago, I started a drawing-a-day project on Instagram as a fun creative pursuit, while I was working at the marketing job that I'd landed with my wild-ride resume. The project grew in every direction and eventually I didn't have time for my office job anymore; I quit to become a full-time illustrator/writer.

Alongside tremendous gratitude, wonder, and shock, I thought “Well I guess this is the rest of my life now." I admit that other dreams felt neglected in the process. What about becoming a fashion designer? What of the classroom I'd been decorating in my head since I decided I wanted to be a teacher? What do I do with the teach-yourself-Farsi books for my journalism job?

This was the real reason it was so hard to commit to a path: Picking a lane meant abandoning the others.

Sometimes grief intertwines itself in our most 'successful' moments, and I felt a little sad to be giving up my identity as person with a lot of potential though it's totally unclear what that potential is. At times I felt a little stuck in someone else's dream, whereas I wanted to keep experimenting with my own unfinished, perpetually zigzagging life.

Not only did I inadvertently buy into arrival fallacy (the idea that once we attain a goal, we'll have a lasting sense of achievement and happiness), but I also failed to remember what I learned years earlier at my marketing job interview:

I was bringing my full self to this new position. I never wanted to erase or ignore the office job, the grad school goal, the fashion writing, the retail years. It would have been easier from a self-promotion perspective to commit to saying "I'm an illustrator and I've always wanted to do that" but that wasn't true at all; it was simply something I was trying for a time.

Even then, I couldn't pick a lane.

I still have trouble articulating what exactly it is that I do, especially as my job has changed and I've changed. I call myself a writer but I get tripped up when asked, "What do you write about?" I wince the same way I used to when I'd list all the jobs on my resume and fail to see a copacetic narrative.

Whereas many of my writer/artist peers have a snappy sentence to describe what exactly they offer, I remain uncertain. Most of the time, this brings up massive insecurities for me, but other times I find it tremendously liberating, as I continue to swerve lanes and check out some backroads.

While I still find myself occasionally longing for MY ONE TRUE PASSION (or just a succinct one-line bio), I've come to appreciate what I call creative composting: using all the 'scraps' of my life to make fertile soil for whatever comes next. It's harder to describe, and harder for others to understand, but it feels more true.

In a newsletter from George Saunders, he writes about all his miscellaneous early influences. While it's tempting to list the things we WISH had formed us, or simply whittle down our influences to the most literary/elevated/cool ones, it's much more interesting to "bless certain influences that we haven’t allowed to the table yet...Those influences are in us, waiting to be used, and wanting to be used."

I love when authors and artists boldly admit that their idols run the gamut from athletes to action heroes to screenwriters of sappy movies to children's book heroines to an obscure historian, because that feels so real to the human experience. Most of us get inspiration from all over the place, just as most of us wander all over the place even if we insist otherwise.

George elaborates:

The point is really this: to write a good story takes everything we have and everything we are. We tend to think, “I am in control here, and will honor that in which I have come to love and believe, about writing and art and life.” But, in my experience, that is a too-controlled and too-controlling mindset, saying, as it does, that you, the writer, will decide what is needed when, in fact, it’s the story that is going to decide how much is needed. And what will be needed, if the story is going to be good, is: everything, all that you are, even those parts you don’t like or usually exclude.)

Just as the detours on my resume formed me as much or more as the fancier bullet points, my scattered interests and influences are all welcome at my desk too. I'm now a bit more comfortable with picking a lane, knowing that I'm bringing all my experiences from stretches on other roads along with me.

(I have no business using this metaphor as I can't drive, but you get it?)

This weekend, I'm taking myself on a solo retreat to work on a proposal for a book that I can only describe as philosophy, natural history, self-help, spirituality, and memoir...combined.

I feel self-conscious that I can't commit to one category, but that's nothing new for me. Someone once told me, "Don't just write the book you wish existed; write for the bookshelf you wish existed." In other words, bring your whole self into what you're creating and you might end up making a new genre.

When I happily welcome the parts of myself that I suspect don't have any 'use,' I tell better stories and I make better friends and I live better days. It's not as sell-able, not as explain-able, but the people who get it will get it—and even appreciate it. Or so I tell myself as I begin my five-genre book this weekend.

PS. Help me serve you better! Kindly fill out this survey so I can learn more about you and why you read this newsletter. Thank you so much, and THANK YOU to those who have filled it out already—I've loved reading your answers!!

Welcome to Out of the Blue, a weekly reflection on something that's caught my attention, and an attempt to learn deep lessons from the shallow and light wisdom from the dark. If you haven't subscribed yet, sign up for free here!