Your feelings aren't pure

"The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house" -Audre Lorde

In January 2020, I was certain that the year ahead would be forever marked in collective memory by the Australian wildfires that tore through the country's sacred lands.

Those first days of 2020, everything I did felt so trivial: going out, or not going out; enjoying myself, or letting the news sink my energy. A country was on fire, and I was going about my business.

I wanted to publicly acknowledge the disaster but I had nothing to add to the conversation, except for my own feelings, tiny in overall significance yet overwhelming for me:

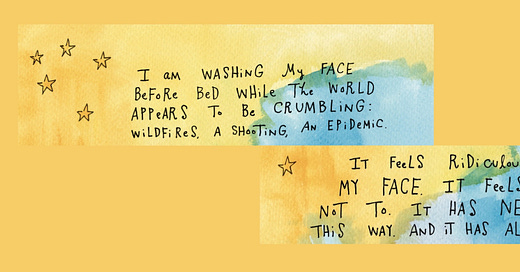

I am washing my face before bed while a country is on fire. It feels dumb to. It feels dumb not to.

It has never been this way, and it has always been this way.

Someone has always clinked a cocktail glass in one hemisphere as someone loses a home in another while someone falls in love in the same apartment building where someone grieves. The fact that suffering, mundanity, and beauty coincide is unbearable and remarkable.

I consider whether it's foolish to want to have children at times such as these and I consider that it's always been "times such as these" and I consider that it's never been worse. Then, in some ways, never been better.

Shouldn't my hypothetical future child have their chance to smell honeysuckle and taste berries?

(These thoughts roll around my head like marbles that were tossed on a smooth surface.)

How is a person supposed to do ordinary things like fall in love when a quick phone scroll is both advertising discount designer socks and informing me that 12 million acres have burned? 12 MILLION?!

I despair with an exhale, then I refuse to despair, with an inhale. ("Despair is a tool to control us.")

I scroll some more: A new baby, a new album, a flower, firefighters. A threatened world holds so much.

"I must choose between despair and energy—I choose the latter." -Keats

What does it look like to state in the midst of smoke: I choose energy?

For starters, I choose to finish washing my face.

Then, I choose to look: not away, but toward.

I choose to trust: First, in goodness. Then, in people I know. Then, in people I've never met. Always, in myself.

I choose to eat less meat/dairy even though, yes, there are zillions of other ways to help the planet but that should never stop me from doing one thing, and I care about cows, and koalas, and my cat and the pigeons she watches.

I choose to do the things that I may think are too insignificant to matter, because sometimes protesting is an act of grieving and small choices toward energy keep me from despair.

I choose to enjoy. I choose a new record. I choose to keep a $5 bill in my pocket for someone who may need it. I choose to text a friend "I'm sending lots of love Down Under" and I choose to buy from Aboriginal-owned businesses and I choose to show up at a birthday party

because grief and celebration often happen in the same night.

Since January 2020, there have been many times I’ve felt silly about washing my face. Two months later that same year, I would attend a lighthearted Zoom Happy Hour—still a novelty in those early pandemic days—as ambulance sirens wined outside, lined up in front of a hospital at full capacity.

Many of us have also been on the opposite side of this; in my bleakest moments of grief and pain I’ve watched people blithely jog down the block and wonder how they were capable of such normalcy as my own slippery world slithered out of my grasp. Then again, it would bewilder me if they didn’t; If I were happy and healthy, I, too, would be blithely jogging. Or, at least, something to that effect.

The coexistence of two seemingly disparate emotions may shock us, yet we’ve proven how it’s done over and over: Our enraged bodies are still tender enough to scratch a dog's ears and our devastated hearts still beat wildly at the sight of mountaintops from a plane window.

We are capable of a whole landscape of feelings that, somehow, don’t cancel each other out. Sorrow can’t be erased by pleasure and even true joy isn’t fazed by grief; they are companions who have a lot to teach each other.

Yet we still strive toward emotional purity: so that we allow ourselves only one feeling at a time, or disallow certain feelings at all. Then we can function effectively in a societal framework that prizes logic above how it feels.

But the fact is, feelings can not be gotten rid of or canceled out or wiped off. When it comes to human emotions, there is no purity.

Purity is a concept I’ve thought a lot about in my life.

When I was a teenager, I read a book called ‘I Kissed Dating Goodbye,’ a rulebook for Purity Culture: a subculture of evangelical Christianity based on extreme rules of abstinence and a strict, stereotype-based binary of gender.

The book, with all its earnest suggestions to only date in group settings to avoid 'temptation,' implied that girls’ bodies were evil and boys’ minds were evil. Girls shouldn't provoke, and boys’ minds shouldn't be provoked. One tarnish (a stray ‘impure’ thought, or a hemline a bit too short), and we’d be forever unclean.

As is the case with any community, Purity Culture had its own shared vocabulary and set of correct actions, which all created a public semblance of spiritual cleanliness—of utmost importance in the community.

We were free and encouraged to judge each other, so appearing pure was just as important as actually being pure.

I'm still surveying the damage Purity Culture caused to my relationship with the Divine and with my own body, but here’s what I know for a fact: The concept that I had to purify my thoughts, words, and actions in order to partake in something I felt strongly about, was profoundly destructive.

I came to believe that God wanted me to be as quiet, invisible, and inactive as possible. If I never did anything, then I would be blemish-free. If I never spoke, I could never accidentally provoke. God’s love (and acceptance from church folks) was contingent on my complete and total purity, and the only way I could be really pure is to give up any inkling that my body is my own. It was far too risky to experiment with my own humanity.

Purity Culture was my first lesson in dualism: The idea that two things can't exist at the same time. You were pure or you weren't, you loved God or you didn’t. Any stain on either side would force companions into opponents: It’s this or that. Never mind any room for the spiritual juiciness of wonder, mysticism, questions, or intuition.

Purity culture treated people more like flashlights than humans, with on/off switches that would produce a very dissatisfying glow when illuminated.

Purity isn’t interested in how it feels. It’s about holding yourself back, and, therefore, not being honest. Purity gives us the illusion of safety from judgment, but is that any way to connect with others and with the Divine? Definitely not, and, as Audre Lorde famously wrote, Your silence will not protect you.

Audre Lorde was a profound influence on my favorite teacher of transformative justice, Adrienne Maree Brown. Pleasure Activism is a gorgeous exploration of how centering our true feelings and deepest nature influences how we show up in the world and how we are active in justice. She writes:

“We need radical honesty—learning to speak from our root systems about how we feel and what we want. Speak our needs and listen to others’ needs….The result of this kind of speech is that our lives begin to align with our longings, and our lives become a building block for authentic community and ultimately a society that is built around true need and real people, not fake news and bullshit norms.”

Purity is a bullshit norm. Purity is rigid. Purity is aggressive. Purity upholds a fraction and denies wholeness. Purity is a tool to limit us, prioritizing lists over true needs.

I left Purity Culture long ago, but I've seen a new form of it emerging online:

How dare you water your plants when there’s a war going on? If you're not angry 24 hours a day, you need to look at yourself in the mirror. How self-centered can you be to spend $3 on a cup of coffee instead of donating it?

These extreme/fake examples aren't far off from what I've actually read! This brand of emotional strictness gives me flashbacks to the rigidity of evangelical purity culture, which bred dishonesty because it was all about performing one sliver of our humanity according to what was acceptable in public.

I also get flashbacks to the impulse to stay invisible, quiet, and inactive. A lot of us feel safer from judgment that way. The problem with allowing ourselves only one response at a time is that it ends up shaming us into inaction. It makes us believe that our small actions aren’t enough, because it’s a dualistic mentality: all, or nothing.

When we believe that our orientation toward the world must be perfectly pure, e.g. “If we really care about this news story, we will only be able to react in one way,” we are partaking in a new purity culture that is also damaging to our bodies: the keepers of all our wonderfully chaotic hopes, cares, feelings, observations, and inklings—the very things that drive our empathy and fuel our bravery.

Adrienne Maree Brown writes, “Pleasure activism is the work we do to reclaim our whole, happy, and satisfiable selves from the impacts, delusions, and limitations of oppression and/or supremacy.”

When I force myself to remain emotionally pure, I feel like I’m giving in to the limitations of oppression rather than standing against them. I’m not able to actually show up for justice because I’m only bringing a sliver of myself.

I've come to learn that my feelings are invitations to action, not blocks in the way. What if my sadness is useful? What if my desire can nudge me to forward movement? What if I can use all the passion that overflows when I'm joyful into reimagining a new future? What if my delight can explode into creativity for the good of others? What if my calmness invites me to transformation?

As Rabbi Jay Michaelson wrote about emotions and justice, “Sadness does not disappear, but it is included in a serene and compassionate embrace. The endlessly hard work of pursuing justice is somehow interfused with the happiness that does not depend on conditions.” He reminds us that we are invited to fully engage with the world, which doesn’t mean ignoring our own feelings but folding them into our work.

Sadness and happiness belong in justice because sadness and happiness belong in our selves: potent flavors in the wild stews that we are. We can carry sorrow in our pocket at a party, at the movies, while planting tulips, and while imagining and working toward a war-less world. We can erupt with excitement and yearning while talking with friends about creativity in the climate crisis.

Perhaps one of Purity Culture's greatest harms is that it keeps us from paying attention (my favorite spiritual practice). Purity disconnects me from my own thoughts and longings and demands that I dismiss so much of the humanity in others. It presupposes how I should act and how others should act, ignoring so much of what goes into luscious human complexity.

When I emerged out of purity culture, I started paying relentless attention and thus found an overwhelming richness of being fully alive. I developed intentionality (rather than dogma) around desire; curiosity (rather than fear) about what other people believe.

I’m much more engaged with the world because I’m not afraid to mess up. I’m not afraid of accidentally hearing an opinion that threatens my own worldview; I’m not thinking about how to win people over to my side but how to actually listen. Acceptance and love for my own inner world has given me much more acceptance and love for the inner worlds of others.

Believing that we are capable of only one emotion is likewise detrimental to the discipline of paying attention. Paying attention admits that the news affects and shapes us, and that there are many parts of our kaleidoscope soul asking to be seen at the same time. Paying attention releases us into the richness of being fully alive.

The world feels so sharp and crooked right now. I, for one, am at a complete loss, and my feelings are all over the place—as they should be. But I'm appreciating my little moments of bliss like energy bars for the road ahead, and embracing my sadness in all its wisdom.

"That greater greater self is in there waiting—in each of us," writes Adrienne Maree Brown. "And as we release ourselves to be ourselves, that greater greater society and economy and existence become possible."

Your feelings aren't pure, but they are invitations to envision a greater greater world. There is nothing wrong with feeling delight during eras of utter gloom, and nothing incorrect about including the softness of sorrow in your hard work. That greater greater self envelopes all of it: the anguish, the absurdity, the daydreams, the cocktail clinks.